Intersectionality and Ecofeminism

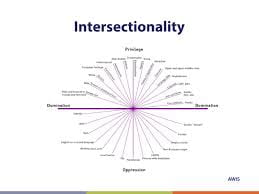

Intersectionality in Feminism is an approach that encompasses all oppressions and the fact they are all interconnected. Kimberle’ Crenshaw first defined it  as a “metaphorical and conceptual tool used to highlight the inability of a single-axis framework to capture the experiences of black women” (Kings). Intersectionality dissects the interconnectedness of race, class, gender, disability, sexuality, caste, religion, age, etc. in relation to discrimination, oppression, and women. “People experience multiple aspects of identity simultaneously and the meanings of different aspects of identity are shaped by one another” (Kang, Lessard and Heston). Crenshaw developed this term in 1989. It was a way for black women to express how they were discriminated against by race and gender and further by class, and economic status. Crenshaw and Patricia Hill assert that environmental movements don’t take black women struggles into account and therefore, “there is no movement that truly addresses the intersectional oppression black women face from sexism and environmental racism” (Cain). The theory of intersectionality is specific but flexible and can be used in a variety of ways when discussing oppression in feminism.

as a “metaphorical and conceptual tool used to highlight the inability of a single-axis framework to capture the experiences of black women” (Kings). Intersectionality dissects the interconnectedness of race, class, gender, disability, sexuality, caste, religion, age, etc. in relation to discrimination, oppression, and women. “People experience multiple aspects of identity simultaneously and the meanings of different aspects of identity are shaped by one another” (Kang, Lessard and Heston). Crenshaw developed this term in 1989. It was a way for black women to express how they were discriminated against by race and gender and further by class, and economic status. Crenshaw and Patricia Hill assert that environmental movements don’t take black women struggles into account and therefore, “there is no movement that truly addresses the intersectional oppression black women face from sexism and environmental racism” (Cain). The theory of intersectionality is specific but flexible and can be used in a variety of ways when discussing oppression in feminism.

Ecofeminist’s argue that they have been applying the concepts of intersectionality before 1989.

Ecofeminism says, “A healthy, balanced ecosystem, including human and nonhuman inhabitants, must maintain diversity” (Bookchin), diversity that encompasses all living things. Ecofeminism surfaced in the 1970’s and 1980’s and claims to have had an understanding of intersectionality before the term was coined. Similar to the principles of intersectionality, ecofeminist’s strive to demonstrate how the lives of humans are interconnected in the environment, specifically women in. Further, “classism, sexism, heterosexism, naturism, and speciesism are all intertwined” (Hobgood-Oster). For example, Ynestra King contests that nature and culture are separate thus making an intersectional connection to ecofeminism. Similarly ecofeminist principles suggest an intersectional approach believing, “life is an interconnected, web not a hierarchy” (Bookchin). Ecofeminist principles support diversity and oppose domination and violence. Most central to ecofeminism is that women and nature are oppressed by patriarchal structures. Ecofeminist show the connections between all forms of domination, including the domination of nonhuman nature (Bookchin).

Black Women and Ecofeminism

Despite ecofeminism’s inclusion of an intersectional approach black feminist critique that ecofeminist principles fail to recognize the struggles of black women and their environmental concerns.  In “Women of Color, Environmental Justice and Ecofeminism”, Dorceta Taylor compares how the mainstream environmental movement and the ecofeminist movement focus primarily on the middle class and white women rather than include the black community (Cain). Although ecofeminist seek to eradicate the patriarchal and economic forms of oppression that degrade women and the environment Taylor says black women of degraded communities are “the waste products of capitalist production and excessive consumption” (Cain). This argument would suggest that ecofeminism is not intersectional its approach.

In “Women of Color, Environmental Justice and Ecofeminism”, Dorceta Taylor compares how the mainstream environmental movement and the ecofeminist movement focus primarily on the middle class and white women rather than include the black community (Cain). Although ecofeminist seek to eradicate the patriarchal and economic forms of oppression that degrade women and the environment Taylor says black women of degraded communities are “the waste products of capitalist production and excessive consumption” (Cain). This argument would suggest that ecofeminism is not intersectional its approach.

However, the interconnected web of ecofeminism connects women and the environment as well as race, class, sexuality, religion, disability, species and age. Martin Luther King Junior said, “No one is free until we are all free.” This quote demonstrates that black people or white people aren’t free until the other is free. According to Kings, “Intersectional ecofeminism builds upon this foundation by further postulating that the ‘freedom’ of humanity is not only reliant on the freedom of nature and women, but it is also reliant on the achievement of liberation for all of those at intersecting points on along these fault lines” (Kings).  Ecofeminism’s interconnected web has been looking at the connection of women and the environment in an intersectional way and has evolved to include more ways we can look at ecology and feminism in relation to different degrees of oppression and will continue to evolve. To preserve diversity ecofeminist must look at all participants in an intersectional way. Although intersectionality may not offer a complete solution to issues of difference it can help us to explore ways that different forms of oppression impact those who would otherwise be ignored.

Ecofeminism’s interconnected web has been looking at the connection of women and the environment in an intersectional way and has evolved to include more ways we can look at ecology and feminism in relation to different degrees of oppression and will continue to evolve. To preserve diversity ecofeminist must look at all participants in an intersectional way. Although intersectionality may not offer a complete solution to issues of difference it can help us to explore ways that different forms of oppression impact those who would otherwise be ignored.

Bibliography

Bookchin, Murray. The Ecology of Feminsm and the Feminism of Ecology. 27 Oct 2019. 26 March 2020 <https://libcom.org/library/ecology-feminism-feminism-ecology>.

Cain, Cacldia. “The Necessity of Balck Women’s Standpoint and Intersectionality in Environmental Movements .” Black Feminist Thought 2016 (2016).

Hobgood-Oster, Laura. “Ecofeminism: Historic and International Evolution.” 31 January 2020 <http://users.clas.ufl.edu/bron/pdf–christianity/Hobgood-Oster–Ecofeminism-International%20Evolution.pdf>.

Kings, A.E. “Intersectionality and the Changing Face of Ecofeminism.” Ethics and the Environment 22.1 (2017).

Annotated Bibliography

Kang, Miliann, et al. Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies . Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, 2017.

The section of this book on Intersectionality is part of a larger category of gender studies titled, “Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies”. This section details the concept of intersectional analysis. The problem that can be run into is when issues that surround feminism stop at gender. Intersectionality is a theory that can further explore the interconnected issues that apply to feminism. The book on a whole explores other issues that impact feminism such as binary systems, institutions, culture, work-family policy, economy and social movements.